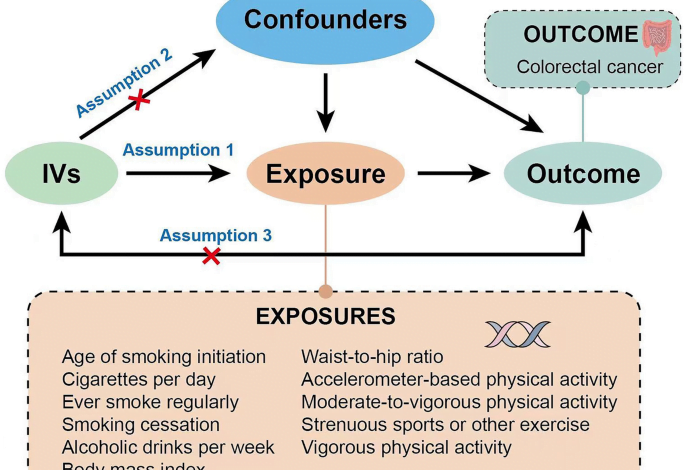

Unhealthy lifestyle factors and the risk of colorectal cancer: a Mendelian randomization study

To date, the prevention of colorectal cancer remains a challenging issue. In this study, we utilized a two-sample Mendelian randomization to investigate the causal association between unhealthy lifestyle factors and the risk of colorectal cancer in European populations. The results suggest that a higher WHR is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, and smoking is potentially associated with the incidence of colorectal cancer. However, no definitive evidence was found to support an association between alcohol consumption and physical activity with the incidence of colorectal cancer.

Smoking

Our study found a potential association between smoking and an increased risk of colorectal cancer. A systematic review of six cohort studies and fifteen case–control studies in the Japanese population suggested that smoking may contribute to the increased incidence of rectal cancer, but there was insufficient epidemiologic evidence to prove an association between smoking and colon cancer19. Another prospective study, which included 120,000 Cubans, investigated the relationship between different smoking ages and premature mortality. The results showed that smoking could lead to an increased incidence of various digestive tumors, including colorectal cancer, with the effect being most pronounced in individuals who began smoking before the age of 10. The risk of premature mortality in these individuals was approximately 2.51 times that of non-smokers20. A meta-analysis of 160 observational studies examining the association between smoking and the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer concluded that smoking was significantly associated with the incidence of colorectal cancer, with a more pronounced effect in rectal cancer21. Despite these findings, the specific mechanism by which smoking mediates colorectal cancer remains unclear. A recent study indicated that smoking may increase the intestinal levels of taurodeoxycholic acid (TADC) by inducing gut microbiota dysbiosis. TADC can activate signaling pathways such as MAPK/ERK, IL-17, and TNF, leading to tumorigenesis. Furthermore, intestinal barrier dysfunction caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis could further facilitate this process22. Our Mendelian randomization analysis suggests a possible association between smoking and colorectal cancer, emphasizing the importance of tobacco control in reducing the long-term burden of this disease.

Alcohol consumption

Our study did not find a causal association between alcohol consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer. This conclusion contrasts with the results of various observational studies. A case–control study examining the relationship between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer risk in the Mediterranean population concluded that moderate alcohol consumption (12–25 g/day) was a protective factor for colorectal cancer (OR = 0.35; 95% CI 0.16–0.74), while heavy alcohol consumption (more than 48 g/day) was a risk factor for colorectal cancer (OR = 3.45; 95% CI 1.35–8.83). This effect was closely related to the type of wine consumed, with moderate red wine consumption thought to reduce the risk of many types of cancer, including colorectal cancer7. Additionally, a meta-analysis of five case–control studies and eleven prospective nested case–control studies involving 14,276 colorectal cancer cases and 15,802 controls supported this conclusion23. However, a cohort study of dietary inflammatory potential and the risk of colorectal cancer showed that for some specific populations (pro-inflammatory diet), abstaining from alcohol was a risk factor for colorectal cancer (OR = 1.02, P = 0.002)24. Although our MR analysis found no causal association between alcohol consumption and colorectal cancer, the potential effect of alcohol consumption on colorectal cancer cannot be entirely excluded. Our study focused solely on a European population, so further research is necessary to confirm these findings.

Physical activity

While we did not find a causal association between physical activity and colorectal cancer in this study, the role of physical activity in cancer prevention and treatment is well established. A recently published review on the mechanism of exercise in cancer prevention and therapy suggested that physical activity could reduce cancer risk by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, regulating tumor metabolism and the immune microenvironment, and inducing apoptosis25. Numerous observational studies have also concluded that physical activity reduces the risk of colorectal cancer26,27,28,29,30. Therefore, despite the uncertainty in our MR analysis regarding the causal association between physical activity and colorectal cancer, the potential benefits of exercise should not be overlooked. Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to provide a more comprehensive MR analysis.

Obesity

Obesity has been defined by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a risk factor for colorectal cancer31,32, a view confirmed by numerous observational studies. BMI and WHR are both used to evaluate obesity. BMI primarily assesses overall obesity, while WHR evaluates central obesity. BMI is currently the most commonly used indicator to measure obesity. However, a cohort study including 387,672 UK participants concluded that WHR is more powerful and robust in predicting morbidity and mortality than BMI33. A review summarizing the epidemiological and pathophysiological evidence on the relationship between obesity and cancer showed that WHR was more strongly associated with the risk of cancer than BMI34. In addition, numerous studies have demonstrated that WHR has a stronger prediction ability than BMI in diseases such as diabetes, prostate cancer, cardiovascular risk, cirrhosis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease35,36,37,38,39,40. For colorectal cancer, central obesity is more closely associated with the disease than overall obesity. A cohort study of 134,255 Chinese participants investigating the association between weight, fat distribution, and colorectal cancer risk concluded that although both BMI and WHR were significantly associated with the risk of colorectal cancer, in the analyses stratified by WHR and BMI, the positive association between BMI and CRC weakened while that of WHR was still significant41. In this study, we further confirm the causal association between higher WHR and an increased risk of colorectal cancer through two-sample Mendelian randomization. This conclusion suggests that fat distribution should be the focus of future studies on the association between obesity and colorectal cancer rather than total fat.

Our study has several strengths: firstly, we utilized two-sample Mendelian randomization as the study method, which ranks second only to RCTs in the level of causal inference of evidence-based medicine. This method avoids the influence of confounding bias and reverse causality, making the inference of causality more reliable. Additionally, Mendelian randomization is less costly and more accessible than RCTs. Secondly, the SNPs used in our study are all obtained from published genome-wide association study data analysis, which ensures a strong correlation between SNPs and exposure. Thirdly, the data used in this study are all from populations of European ancestry, and the SNPs for exposure and outcome were derived from different sources, thereby avoiding population stratification bias and sample overlap.

Our study also has some limitations. Firstly, our research objectives are limited to the European population, necessitating further research to determine if the results are consistent across other racial groups. Additionally, the impact of unhealthy lifestyle factors on colorectal cancer may vary across different anatomical sites, pathological subtypes, and genders. However, due to the limitations in data availability, there are no suitable GWAS colorectal cancer datasets available for conducting subgroup analyses. A more comprehensive study including different subgroups of colorectal tumors will be implemented in the future. Secondly, the occurrence of most diseases, especially cancers, requires the synergistic effect of multiple genes and environmental factors. Mendelian randomization can only investigate the influence of a single gene and cannot comprehensively consider the complexity of multi-gene synergy. In addition, some potential confounders between the exposure and outcome and an insufficient sample size may bias the conclusion. Therefore, a large number of follow-up studies are needed to further refine the findings of this study.

All in all, this study indicated that higher WHR is a risk factor for colorectal cancer, and smoking is potentially associated with the colorectal cancer risk. From the perspective of basic and clinical research, we suggest that future research on colorectal cancer should not only consider BMI but also give significant attention to WHR. From the perspective of Epidemiology and public health, this study highlights the importance of quitting smoking and maintaining healthy weight and provides a reference for the prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer in the future.

Source link